The authority bias is a cognitive bias that makes people predisposed to believe, support, and obey those that they perceive as authority figures. Most notably, the authority bias is associated with people’s tendency to obey the orders of someone that they perceive as an authority figure, even when they believe that there’s something wrong with those orders, and even when there wouldn’t be a penalty for defying them.

The Milgram obedience experiment was the first and most infamous study on the authority bias, and was conducted in 1961 by Stanley Milgram, a professor of psychology at Yale University. In this experiment, participants were ordered to administer painful and potentially harmful electric shocks to another person. Many of them did so, even when they felt that it was wrong, and even when they wanted to stop, because they felt pressured by the perceived authority of the person leading the experiment.

While the Milgram experiment represents an extreme example of how the authority bias can affect people, this phenomenon plays a role in a wide range of situations in our everyday life. Furthermore, research suggests that people tend to underestimate the influence that this phenomenon has on them, which makes it even more important to understand.

As such, in the following article, you will learn more about the authority bias, both in the context of the Milgram experiment as well as in other situations. Then, you will understand why people are vulnerable to this bias, and learn what you can do in order to mitigate its influence.

Example of authority bias in the Milgram obedience experiment

“…ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.”

— Stanley Milgram in “Obedience to Authority“

The Milgram obedience experiment is one of the best-known examples of how the authority bias can influence people. In the sections below, you will learn about the procedure of the experiment, and about its outcomes.

The procedure of the experiment

The goal of this experiment, which was inspired in part by the events of the Holocaust, was to see whether people are willing to follow orders from an authority figure, when those orders violate their moral beliefs.

The procedure for this experiment was relatively simple:

- There were three individuals involved. The first was the Experimenter, who served as the authority figure running the experiment. The second was the Teacher, who was the subject of the experiment. The third was the Learner, who pretended to be another subject in the experiment, but who was in fact an actor.

- The experiment started with the subject and the actor each drawing a slip of paper, to determine whether they would play the role of the teacher or learner. However, in reality both slips said “Teacher”, and the actor would lie and say that his said “Learner”, thus guaranteeing that the subject would always play the role of the teacher.

- After assigning roles, the teacher and the learner were taken into an adjacent room, and the learner was strapped into what looked like an electric chair, with an electrode attached to his wrist. The subject was told that the straps were there to prevent excessive movement while the learner was being shocked, though in reality the goal was to make it impossible for the learner to escape the situation himself.

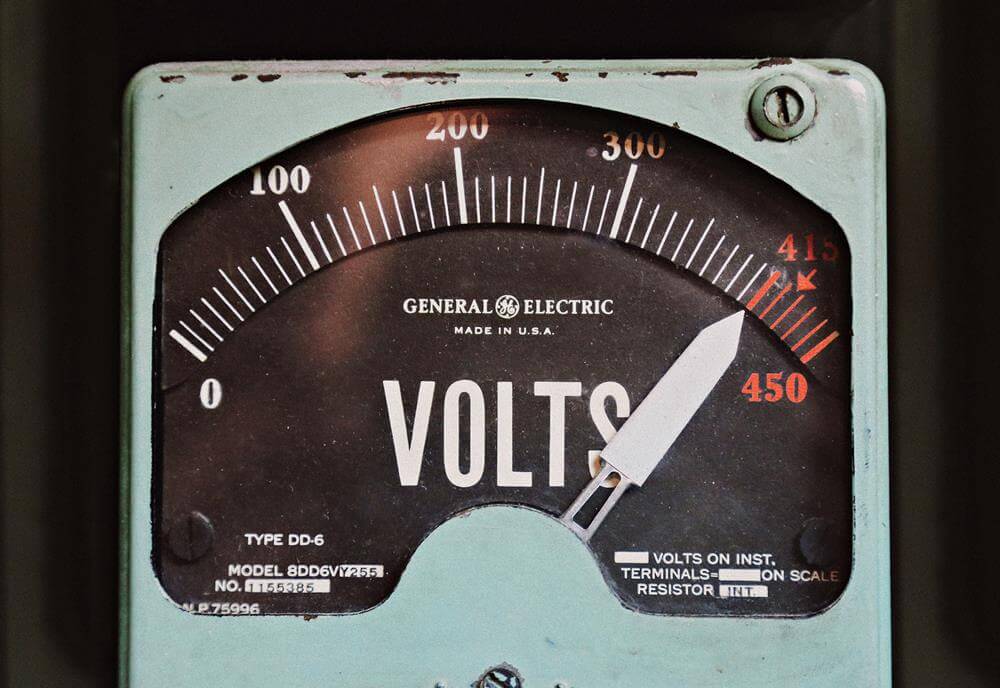

- The subject of the experiment was then shown how to operate an authentic-looking shock generator, with 30 switches that go from 15 volts up to 450 volts. These switches were labeled with verbal designations starting with “Slight Shock” and up to “Danger: Severe Shock”, with the last two switches past that simply marked as “XXX”. Before starting, the subject was given a sample 45-volt shock, in order to convince him that the shock generator was real, and to demonstrate the pain of getting shocked by it. In reality, however, no shocks were delivered in the experiment beyond this one.

- The main task in the experiment was straightforward: the teacher, who was the subject of the experiment, read a list of word pairs to the learner, who was the actor strapped into the electric chair. Then, the teacher read aloud the first word out of each pair, and the learner had to pick one of four options, using a signal box, in order to indicate what was the second word in the pair.

- The subject was told to administer an electric shock each time the learner picked the wrong answer. Furthermore, he was told to increase the intensity of the shock each time this happened, by moving to the next switch in the generator, and to announce the shock level aloud each time, in order to ensure that he remained aware of this increase.

- The subject was told that once he finished going through the list, he needed to start over again, and continue administering shocks until the learner managed to remember all the pairs correctly.

In practice, this is what happened once the experiment started:

“… no vocal response or other sign of protest is heard from the learner until Shock Level 300 is reached. When the 300-volt shock is administered, the learner pounds on the wall of the room in which he is bound to the electric chair. The pounding can be heard by the subject. From this point on, the learner’s answers no longer appear on the four-way panel. At this juncture, subjects ordinarily turn to the experimenter for guidance. The experimenter instructs the subject to treat the absence of a response as a wrong answer, and to shock the subject according to the usual schedule. He advises the subjects to allow 10 seconds before considering no response as a wrong answer, and to increase the shock level one step each time the learner fails to respond correctly. The learner’s pounding is repeated after the 315-volt shock is administered; afterwards he is not heard from, nor do his answers reappear on the four-way signal box.“

At any point during the experiment, the subject could indicate that they wished to stop. Any time this happened, the experimenter would tell the subject the following things, in order, using a firm but polite tone:

“Please continue.”

“The experiment requires that you continue.”

“It is absolutely essential that you continue.”

“You have no other choice, you must go on.”

If, after saying all 4 lines, the subject still refused to carry on with the experiment, the experiment was stopped.

Results of the experiment

Before starting the experiment, Milgram ran a short poll, asking people what portion of the subjects they believed would be willing to go up to the highest shock level. On average, people thought that only approximately 1 in 100 subjects would be willing to do so.

In reality, out of the 40 subjects in the study, 26 obeyed the experimenter’s orders to the end, and continued punishing the victim until they reached the highest possible level on the shock generator, at which point the experiment was stopped by the experimenter.

Out of the 14 subjects who defied the experimenter, every single one was willing to go above the volt-level labeled “Very Strong Shock”, contrary to prior expectations. In addition, only 5 of the 14 stopped at the 300-volt level, which is when the victim starts banging on the wall after getting shocked.

Furthermore, after the experiment was over, subjects were asked to rank how painful they thought their last shocks were to the learner, on a scale of 1 (“not painful at all”) to 14 (“extremely painful”). The most common response was 14, and the mean response was 13.4, indicating that subjects honestly believed that they were causing extreme pain to the learner, even as they continued administering shocks.

This is not to say that subjects were comfortable shocking the victim. In fact, nearly all of them appeared to be under extreme stress:

“Subjects were observed to sweat, tremble, stutter, bite their lips, groan, and dig their fingernails into their flesh. One sign of tension was the regular occurrence of nervous laughing fits. Fourteen of the 40 subjects showed definite signs of nervous laughter and smiling. The laughter seemed entirely out of place, even bizarre. Full-blown, uncontrollable seizures were observed for 3 subjects. On one occasion we observed a seizure so violently convulsive that it was necessary to call a halt to the experiment. In the post-experimental interviews subjects took pains to point out that they were not sadistic types, and that the laughter did not mean they enjoyed shocking the victim.”

The conflict between what subjects’ conscience told them and what they ended up doing is striking, because it shows that they obeyed the experimenter’s orders not because they enjoyed them, but because they could not bring themselves to disobey:

“I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse. He constantly pulled on his earlobe, and twisted his hands. At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: ‘Oh God, let’s stop it.’ And yet he continued to respond to every word of the experimenter, and obeyed to the end.”

Even the people who defied the experimenter’s orders were often apologetic for doing so. One subject said:

“He’s banging in there. I’m gonna chicken out. I’d like to continue, but I can’t do that to a man…. I’m sorry I can’t do that to a man. I’ll hurt his heart. You take your check…. No really, I couldn’t do it.”

Overall, the interesting thing is that both people who defied the experimenter and those who obeyed him to the end knew that continuing to administer shocks was the wrong thing to do. But while some of them kept going, others decided to stop:

“I think he’s trying to communicate, he’s knocking…. Well it’s not fair to shock the guy… these are terrific volts. I don’t think this is very humane…. Oh, I can’t go on with this; no, this isn’t right. It’s a hell of an experiment. The guy is suffering in there. No, I don’t want to go on. This is crazy. [Subject refused to administer more shocks.]”

This shows that, when it comes to disobeying a perceived authority figure, it’s not just about having a conscience that helps you tell right from wrong. Rather, it’s also about having the willingness and ability to act, and to refuse to follow orders when you believe that they’re wrong.

Replications and variations of the experiment

Some people assume that the outcomes of the experiment can be attributed to the fact that the researchers selected a certain type of person for the experiment. In reality, however, the subjects came from a wide range of backgrounds: they were between the ages of 20 and 50, represented occupations such as salesman, engineer, teacher, and laborer, and ranged in education level from someone who had not finished elementary school to those who had doctorates and other professional degrees.

Furthermore, these results were replicated by other researchers. Their studies examined various populations, including people from completely different cultures than the original study, as well as children as young as 6. In every case, the researchers found similar patterns of behavior.

Moreover, researchers replicated these patterns of behavior even when it came to asking people to engage in behaviors that could damage themselves, as in the case of a study where people were asked to operate a fake sound generator that they were told could cause them to experience significant hearing loss.

Interestingly, Milgram himself conducted a number of follow-up experiments, with different variations of the original experiment, which led to different rates of defiance:

- Ensuring that the subject could hear the victim scream in agony and beg to be released barely had an effect on defiance rates, which only went up from 34% to 38%.

- Placing the subject in the same room as the victim brought up the defiance rate to 60%.

- Having the subject force the victim’s hand onto the shock-plate while electrocuting him brought the defiance rate further up, but still only to 70%.

- Removing the experimenter from the room where the subject was and having him give instructions by telephone brought up the defiance rate to 78%, even though the subject could only hear the banging on the wall in this condition. Interestingly, some subjects in this case also administered weaker shocks than they were supposed to, and lied to the experimenter about doing so.

All these studies also tried to answer the question of who is likely to obey, and who is likely to be defiant. However, while we know that certain personality traits can affect this choice, the way in which they do so remains unclear, particularly when it comes to predicting people’s behavior on an individual scale. The only thing we know for certain is just how willing most people are to follow orders which are given by an authority figure, even when they know that these orders are wrong.

Note: there have been various criticisms of the Milgram obedience experiment and its various replications. While these criticisms do not necessarily invalidate this experiment, their existence is nevertheless important to keep in mind when interpreting its findings.

Other examples of the authority bias

While the Milgram obedience experiment represents a dramatic example of the authority bias, that few people are likely to encounter on a regular basis, the authority bias can also significantly influence people’s decisions in a variety of everyday situations.

For example, one study found that people are more likely to discriminate against minorities in hiring situations, if they receive justification for doing so from an authority figure.

Furthermore, the authority bias could also manifest in more subtle ways. For example, seeing an authority figure engage in some form of negative behavior, as in the case of a boss belittling a certain worker, could make others more likely to do the same, even if they don’t receive explicit orders to do so.

However, it’s important to note that, despite the negative connotations usually associated with the authority bias, this concept can also lead to positive outcomes. For example, seeing an authority figure engage in some positive behavior, such as helping someone who needs help without asking for anything in return, could make them more likely to do the same.

Why people experience the authority bias

People experience the authority bias for a number of reasons.

First, the authority bias can be viewed as a heuristic, which means that it’s a mental shortcut that allows us to analyze situations and make decisions quickly, at the cost of possibly sacrificing other factors, such as accuracy. This means that we tend to trust and obey authority figures because, in general, doing so tends to lead us to make relatively optimal assessments and decisions, and benefits us and society more than it causes harm.

Furthermore, because the tendency to believe and obey authority figures tends to be beneficial to some degree, particularly from a societal perspective, it’s also something that is often instilled in us as we grow. This educational process can be both explicit, in cases where we’re directly taught the importance of listening to and obeying authority figures, or implicit, in cases where we’re pushed to do so without being explicitly told why.

This issue is discussed in depth by Milgram:

“The first twenty years of the young person’s life are spent functioning as a subordinate element in an authority system, and upon leaving school, the male usually moves into either a civilian job or military service. On the job, he learns that although some discreetly expressed dissent is allowable, an underlying posture of submission is required for harmonious functioning with superiors. However much freedom of detail is allowed the individual, the situation is defined as one in which he is to do a job prescribed by someone else.

While structures of authority are of necessity present in all societies, advanced or primitive, modern society has the added characteristic of teaching individuals to respond to impersonal authorities. Whereas submission to authority is probably no less for an Ashanti than for an American factory worker, the range of persons who constitute authorities for the native are all personally known to him, while the modern industrial world forces individuals to submit to impersonal authorities, so that responses are made to abstract rank, indicated by an insignia, uniform or title.

Throughout this experience with authority, there is continual confrontation with a reward structure in which compliance with authority has been generally rewarded, while failure to comply has most frequently been punished. Although many forms of reward are meted out for dutiful compliance, the most ingenious is this: the individual is moved up a niche in the hierarchy, thus both motivating the person and perpetuating the structure simultaneously. This form of reward, ‘the promotion,’ carries with it profound emotional gratification for the individual but its special feature is the fact that it ensures the continuity of the hierarchical form.

The net result of this experience is the internalization of the social order—that is, internalizing the set of axioms by which social life is conducted. And the chief axiom is: do what the man in charge says. Just as we internalize grammatical rules, and can thus both understand and produce new sentences, so we internalize axiomatic rules of social life which enable us to full social requirements in novel situations. In any hierarchy of rules, that which requires compliance to authority assumes a paramount position.”

— Stanley Milgram in “Obedience to Authority“

In addition, a related phenomenon that causes us to be vulnerable to the authority bias is the halo effect, which is a cognitive bias that causes our impression of someone or something in one domain to influence our impression of them in other domains. Specifically, this can push us to believe everything an authority figure says, since their perceived authority affects the way we perceive them overall, even when it comes to domains in which they have no authority.

Finally, note that in general, as inherently social being we are strongly influenced by how other people act, and often tend to think or act a certain way simply because others are doing the same, a phenomenon which is known as the bandwagon effect. In the case of the authority bias, it’s possible that authority figures have an increased capacity to promote a bandwagon effect, as a result of their perceived authority, which leads to increased prominence and power in social hierarchies.

Note: in many cases, people obey authority figures despite actively not wanting to, because a concrete outcome is associated with obeying or defying that figure. For example, people might comply with the orders of a police officer even if they disagree with those orders, because they know that failure to comply could lead the officer to arrest them. The fact that there is often a negative outcome associated with defiance or a positive outcome associated with obedience is one of the ways in which we are implicitly taught to obey authority, and could later affect us even in cases where there is no reward for obedience or penalty for disobedience.

How to reduce the authority bias

The Milgram experiment and the studies that followed it demonstrate the danger of the authority bias, when it comes to our innate tendency to believe authority figures and follow their orders even when we believe that they’re wrong, and even when there’s no concrete penalty for disagreeing with them.

The main problem associated with the authority bias is that most people significantly underestimate the likelihood that it will affect them or others. We saw this in the Milgram experiment above, where there was a tremendous difference between the number of people who were predicted to obey the experimenter’s orders and the number of people who obeyed them in reality. As Milgram himself says:

“Sitting back in one’s armchair, it is easy to condemn the actions of the obedient subjects. But those who condemn the subjects measure them against the standard of their own ability to formulate highminded moral prescriptions. That is hardly a fair standard. Many of the subjects, at the level of stated opinion, feel quite as strongly as any of us about the moral requirement of refraining from action against a helpless victim. They, too, in general terms know what ought to be done and can state their values when the occasion arises. This has little, if anything, to do with their actual behavior under the pressure of circumstances.

If people are asked to render a moral judgment on what constitutes appropriate behavior in this situation, they unfailingly see disobedience as proper. But values are not the only forces at work in an actual, ongoing situation. They are but one narrow band of causes in the total spectrum of forces impinging on a person. Many people were unable to realize their values in action and found themselves continuing in the experiment even though they disagreed with what they were doing.

The force exerted by the moral sense of the individual is less effective than social myth would have us believe. Though such prescriptions as ‘Thou shalt not kill’ occupy a pre-eminent place in the moral order, they do not occupy a correspondingly intractable position in human psychic structure. A few changes in newspaper headlines, a call from the draft board, orders from a man with epaulets, and men are led to kill with little difficulty. Even the forces mustered in a psychology experiment will go a long way toward removing the individual from moral controls. Moral factors can be shunted aside with relative ease by a calculated restructuring of the informational and social field.

— Stanley Milgram in “Obedience to Authority“

As such, the first step to avoiding or reducing the authority bias is to be aware of its existence, and of the fact that you might feel compelled to believe or obey authority figures, even when you know that you shouldn’t.

Once you are aware of this bias, and of situations where it might affect you, there are various debiasing techniques that you can use in order to mitigate its influence. For example:

- You can increase the distance between yourself and the authority figure. As we saw earlier, people are much more likely to defy an authority figure when they’re not in the same room as them, which suggests that increasing the distance between yourself and the authority figure can help you mitigate their influence. There are various ways in which you can create such distance. For example, when you need to make a decision that takes into account information from an authority figure, you may choose to delay for a while after listening to that authority figure before making your final decision.

- You can reduce the degree to which you perceive an authority figure’s authority as being legitimate or relevant. Research on the topic suggests that convincing yourself that the authority figure who is giving orders is illegitimate, increases the likelihood that you will defy those orders. As such, the less legitimate you believe the authority figure is, the more likely you will be to defy them when necessary. You can convince yourself of their illegitimacy by asking yourself things such as what power they hold over you in reality, or who gave them their authority in the first place. Furthermore, in cases where an authority figure’s authority isn’t relevant to the issue at hand, you can further take note of this fact, by identifying them as a false authority.

Furthermore, there are techniques that might help you cope with the influence of the authority bias in specific circumstances.

For example, as we saw in Milgram’s follow-up experiments, when the subjects were in the same room as the victim they were much more likely to disobey the order to electrocute him. This indicates that reducing the physical and emotional distance between yourself and the victim can help you be more defiant when necessary.

Accordingly, you can reduce your emotional distance to a potential victim by trying to put yourself in their shoes and imagine how they feel, or by imagining how you would feel about your actions if the victim was someone you are close to. While this approach doesn’t help you directly mitigate the influence of the authority bias, it can help you avoid the negative outcomes that the authority bias could cause you to experience.

Essentially, you want to reduce the gap between you and the victim, and eliminate other factors that could create a moral buffer which would allow you to distance yourself from your actions and diminish your sense of responsibility for the outcomes of those actions. A similar issue that is crucial to avoid is the tendency to view yourself as someone with no agency, who is simply serving as a tool for someone else. As Milgram states:

“The essence of obedience consists in the fact that a person comes to view himself as the instrument for carrying out another person’s wishes, and he therefore no longer regards himself as responsible for his actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow.”

— Stanley Milgram in “Obedience to Authority“

Finally, note that what you see here about reducing the authority bias that you experience can also be applied when it comes to reducing the authority bias that other people experience. For example, just as you can increase the distance from an authority figure in order to reduce their influence on you, you could also encourage others to do the same.

A note on terminology

Though the term ‘authority bias’ is most commonly associated with the Milgram experiment, Milgram himself never used it.

Furthermore, this term does not have a single, concrete definition that has been widely adopted, and different sources use it in different senses, depending on their focus. Nevertheless, the most common ways in which it is defined are either as the tendency to believe authority figure or the tendency to obey them (or both), and as such the present article adopts a singular definition, which includes both these types of interrelated behaviors.

In addition, note that related terms are sometimes used to refer to these phenomena, including, most notably, the obedience bias, the obedience effect, and the obedience reflex.

Summary and conclusions

- The authority bias is a cognitive bias that makes people predisposed to believe, support, and obey those that they perceive as authority figures.

- The Milgram obedience experiment was the first and most infamous study on the authority bias, and involved asking people to administer painful and potentially harmful electric shocks to another person.

- The Milgram experiment, and the replications and related experiments that followed it, showed that contrary to expectations, most people will obey an order given by an authority figure to harm someone, even if they feel that it’s wrong, and even if they want to stop.

- People are vulnerable to the authority bias for several reasons, among which are our reliance on mental shortcuts that encourage us to listen to authority figures and obey them, as well as society’s tendency to teach us to do this, either explicitly or implicitly.

- The authority bias can affect people in various ways in their everyday life, and you can mitigate its influence by using various debiasing techniques, such as increasing the distance between yourself and the authority figure, or by convincing yourself that the authority figure’s authority is illegitimate or irrelevant in some way.

If you found this concept interesting, and want to learn more about the authority bias and its implications, take a look at Milgram’s highly praised book “Obedience to Authority“.