The contrast effect is a cognitive bias that distorts our perception of something when we compare it to something else, by enhancing the differences between the things being compared. For example, the contrast effect can make a sweet drink taste bland if you drink it immediately after drinking something sweeter, and can make an overpriced product feel cheap if it’s displayed next to a more expensive product.

Contrast can be created by comparisons that are explicit or implicit, and that are simultaneous or occur at separate points in time. It can apply to various traits, ranging from physical qualities, like color and taste, to more abstract qualities, like price and attractiveness.

The contrast effect plays a role in a wide variety of situations, so it can be highly beneficial to understand it. As such, in the following article you will learn more about the contrast effect, understand why people experience it, and see what you can do to account for its influence.

Examples of the contrast effect

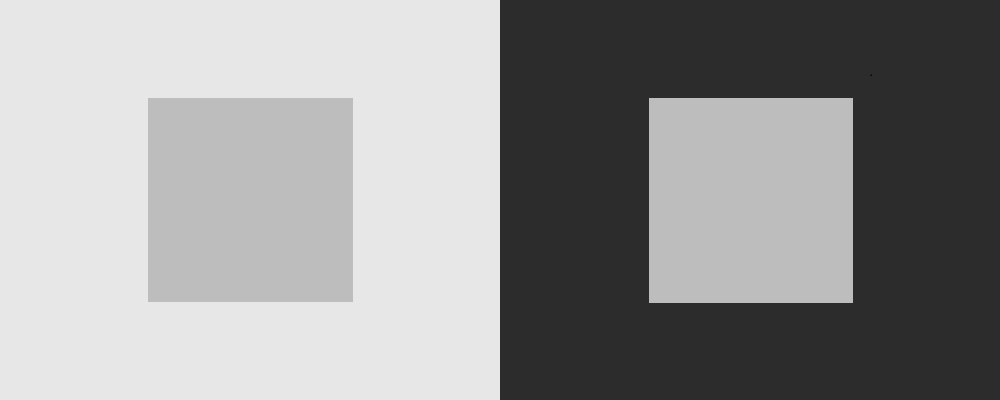

A simple example of the contrast effect appears in the image below, where the grey square that’s placed on the light background appears darker than the grey square that’s placed on the dark background, despite the fact that they’re both the exact same color:

Another example of the contrast effect appears in the literary technique called juxtaposition, in which two elements, such as characters, actions, events, or ideas, are mentioned one after the other to emphasize the differences between them. For instance, consider the following famous example of juxtaposition in literature:

“It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief,

it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light,

it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope,

it was the winter of despair,

we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way…”

— The opening to Charles Dickens’s “A Tale of Two Cities” (1859)

Furthermore, the contrast effect can influence people’s thinking in a variety of other ways. Examples of the influence of the contrast effect include the following:

- Sweet drinks generally taste sweeter if you drink them right after drinking something less sweet, compared to when you drink them right after drinking something sweeter.

- People sometimes feel that they’re more physically attractive after they look at pictures of people who are relatively unattractive.

- Students sometimes feel less confident in their academic abilities when they’re in a class that has a lot of high-performing students.

Note: the last example, of students feeling less confident when they’re in a class with many high-performing students, has to do with a related social phenomenon, called the big-fish—little-pond effect, which is often discussed in the context of the contrast effect. It occurs when people feel better about their performance in some domain when they’re surrounded by people who have relatively low performance in that domain, compared to when they’re surrounded by people who have relatively high performance in the same domain.

Positive and negative contrast effects

In some cases, the contrast effect is categorized as belonging to one of two main types:

- Positive contrast effects. A positive contrast effect occurs when something is perceived as better than it would usually be perceived, because it’s compared to something worse. For example, a positive contrast effect could cause a book cover to appear more interesting than usual if it’s placed next to a book with a boring cover.

- Negative contrast effects. A negative contrast effect occurs when something is perceived as worse than it would usually be perceived, because it’s compared to something better. For example, a negative contrast effect could cause a car to appear cheaper than usual if it’s parked next to an expensive car.

This categorization scheme is generally only used when the trait in question can be evaluated as ‘better’ or ‘worse’. This is applicable, for example, when people assess traits such as attractiveness or intelligence, or factors such as the price of a product.

However, this categorization does not apply in the case of traits that can’t be classified as ‘better’ or ‘worse’, such as color or sound levels.

Why people experience the contrast effect

Because of the wide range of situations and ways in which people can experience contrast effects, there is no single mechanism that is used to explain this phenomenon. However, all explanations of the contrast effect have to do with how our cognitive system intuitively utilizes comparisons when it processes and evaluates information.

For example, when people assess objects or entities that they encounter, they often intuitively compare them to similar objects/entities, or to their memory of them. This can, for instance, make an expensive product feel like it’s reasonably priced, if its price is intuitively compared to that of a more expensive product, even if we’re not interested in the more expensive alternative, and even if we would normally feel that the original product is significantly overpriced.

One notable psychological model that is used to explain the contrast effect is called the inclusion/exclusion model. Under this model, when we evaluate a certain entity based on its features, we have two mental representations: one of the target entity that we’re evaluating, and one of the standard against which we evaluate this target.

Based on this model, a contrast effect can occur when information is excluded from the mental representation of the target entity. This can happen for various reasons, such as because people feel that the information doesn’t properly describe the target, or because they feel that it comes to mind for the wrong reason.

For example, consider a situation where someone is faced with an expensive target product, that is contrasted with a more expensive background product.

In this case, negative information regarding the high price of the target product might be excluded from its representation, as a result of the comparison to the more expensive background product. This, in turn, could cause the target to be perceived in a more positive manner than it usually would when compared against the standard that is used in order to represent products of this type, by making it appear less expensive, and thus more reasonably priced.

Furthermore, this excluded information can sometimes be used during the construction of the standard against which the target is compared. This could mean, for example, that if a certain negative trait of the target is ignored when it comes to the conceptualization of the target and is used instead to enhance the negativity of the standard against which the target is compared, then the target will be rated more positively in comparison.

There are other psychological models that are used to explain the contrast effect, many of which incorporate the inclusion/exclusion model to some degree.

Overall however, while the cognitive mechanisms responsible for the contrast effect are still being investigated, the main reason why people experience this bias is that the process that we use to process and evaluate information often relies on comparisons, regardless of whether or not those comparisons are to our benefit.

Note: the contrast effect is sometimes also referred to as the background contrast effect or the perceptual contrast effect.

Context effects: contrast and assimilation

The contrast effect is generally categorized as one of the two main types of context effects, which are cognitive biases that occur when comparisons with background information affect our evaluation of some stimuli.

The other main type of context effect is called the ‘assimilation effect’. The assimilation effect is a cognitive bias that distorts our perception of something when we compare it to something else, by reducing the apparent differences between them, which makes them appear more similar to one another. For example, the assimilation effect can influence people who see someone acting in a hostile manner, and cause them to view other people’s behavior as more hostile than they would otherwise.

The assimilation effect is therefore similar to the contrast effect, with the difference between the two being that the assimilation effect decreases the perceived difference between the things that are being compared, while the contrast effect increases this difference. Accordingly, the assimilation effect is seen as involving a positive relationship between the context information and the evaluation that people make, while the contrast effect is seen as having a negative relationship between the two.

Note: context effects are often discussed in conjunction with the concept of priming, which is a phenomenon where exposure to a stimulus subconsciously influences our response to consequent stimuli. In addition, another related phenomenon is anchoring, which similarly causes exposure to initial information to heavily influence future decisions.

Psychological mechanisms of assimilation and contrast

A notable psychological model that is used to explain why people can experience both types of context effects is the global/local processing model. This model suggests that global processing, which involves forming relatively abstract representations, leads to assimilation, while local processing, which involves forming more concrete representations, leads to contrast.

The model explains this phenomenon by saying that global processing leads to the inclusion of relevant information, which leads to assimilation by increasing the degree to which traits are perceived as shared between the representation of the target entity and the standard against which it’s compared. Conversely, local processing leads to the exclusion of relevant information, which, as we saw in the section on why people experience the contrast effect, increases the perceived difference between the target and the standard.

Factors leading to contrast versus assimilation

A variety of factors can play a role when it comes to determining whether people experience a contrast effect or an assimilation effect.

For example, one study found that people are more likely to experience an assimilation effect if they focus on the similarities between the different options that are being assessed, while they are more likely to experience a contrast effect if they focus on the differences between them.

Similarly, another study found that when people view pictures of physically attractive people, they tend to rate their own attractiveness as higher afterward if they’re made to feel psychologically close to those people, by being told that they share similar attitudes and values. Furthermore, they display a similar assimilation effect after viewing pictures of unattractive people that they’re made to feel close to. Conversely, when people are shown pictures of people that they don’t feel psychologically close to, they experience a contrast effect, which causes them to feel less attractive after viewing pictures of attractive people, and more attractive after viewing pictures of unattractive people.

How to account for the contrast effect

In some situations, you may want to reduce the degree to which you are influenced by the contrast effect, in order to improve your ability to make rational decisions. This might be the case, for example, if a company’s marketing material is attempting to use contrast in order to make a certain product appear like a good deal, when in reality it’s overpriced.

In such situations, the main way to debias yourself is to break the connection between the main target item that you’re evaluating, and the alternative background items that it’s contrasted against. For example, if you’re trying to evaluate the price of a product, you would want to disconnect it from the background products that are used to justify its high cost.

To accomplish this, there are various approaches you can use. For example, you can:

- Increase the distance between the options. Increasing the distance between the entities that you’re evaluating, in terms of factors such as time and space, can reduce the degree to which you experience a contrast effect between them.

- Add more options. Throwing a variety of additional options into the mix can sometimes reduce the degree to which you notice the contrast between the initial options that you were presented with, because it makes it more difficult to compare them.

- Explain why the comparison is irrelevant. Explaining to yourself why the comparison that you’re presented with is irrelevant, for example by focusing on the absolute price of a product rather than on its relative price, can help reduce the likelihood that you will experience the contrast effect.

In addition, you can use other debiasing strategies, such as slowing down your reasoning process, which will help reduce the degree to which you rely on the flawed intuition that causes you to experience the contrast effect in the first place.

How to use the contrast effect

You can use the contrast effect to your advantage to influence people’s thinking in various situations. For example, you could:

- Highlight an important button in a design by placing it against a drab background.

- Make an expensive product feel reasonably priced by placing it next to a more expensive option.

- Minimize the perceived severity of an issue that you cause by comparing it with more serious issues that happened in the past.

Note that using the contrast effect in this manner can be valuable not only when it comes to influencing other people, but also when it comes to influencing your own thoughts.

For example, consider the example of using the contrast effect to minimize the perceived severity of an issue that you caused. You could do this to influence the opinion of someone related to the issue, in order to reduce the backlash that you have to deal with, or you could do this to influence yourself, and get yourself to feel less anxious about what you did.

When you use the contrast effect to influence people’s thinking in this manner, there are generally several factors that you should pay attention to, in order to create a powerful contrast:

- High relevance. The more related the things you are comparing are to each other, especially in terms of the main trait in question, the more noticeable the contrast between them will be.

- A strong connection. The closer the things that you are comparing are to each other, in terms of factors such as space or time, the easier it will be to notice the contrast between them.

- A large difference. The more different the things that you are comparing are from each other, especially in terms of the main trait in question, the more noticeable the contrast between them will be.

Keep in mind, however, that these are only general guidelines, and the exact implementation of the contrast effect will vary in different situations.

For example, in some cases, going past a certain point when increasing the difference between the available options might actually decrease the likelihood that people will experience the desired contrast effect. This might happen, for instance, if your preferred product is contrasted with a product that is much, much more expensive, which could cause people to avoid comparing the two, or to assume that the cheaper product must be defective in some way.

Summary and conclusions

- The contrast effect is a cognitive bias that distorts our perception of something when we compare it to something else, by enhancing the differences between the things being compared.

- For example, the contrast effect can make a sweet drink taste bland if you drink it immediately after drinking something sweeter, and can make an overpriced product feel cheap if it’s displayed next to a more expensive product.

- Contrast can be created by both explicit and implicit comparisons, and can involve both physical and abstract traits.

- To reduce the contrast effect, you can increase the distance between the things being compared (e.g., by adding space between them or waiting longer before comparing them), add more things into the comparison, or actively consider why the comparison in question shouldn’t matter.

- You can use the contrast effect intentionally, for instance to make a certain option seem more appealing; if you do this, make sure that the things being contrasted are related to each other, easy to compare, and noticeably different.