Memento mori is a Latin phrase that means “remember that you will die”. It is meant to remind you of your own mortality, and of the brevity and fragility of human life.

‘Memento mori’ has been mentioned as an important principle by many people throughout history, and implementing it in your own life can benefit you in various ways. As such, in the following article you will learn more about this principle, and see how you can implement it in practice.

The benefits and dangers of ‘memento mori’

There are a number of benefits to using ‘memento mori’ as a reminder in life:

- ‘Memento mori’ can help you figure out which goals you want to focus on and what you want to do with your life in general.

- ‘Memento mori’ can prompt you to take action, and to avoid needlessly wasting the precious time that you have.

- ‘Memento mori’ can help you put your problems in perspective.

- ‘Memento mori’ can help you cherish every moment in life and feel gratitude toward what you have.

- ‘Memento mori’ can help you avoid hubris, which is a trait that involves excessive pride, self-confidence, and self-importance.

However, while remembering the concept of ‘memento mori’ can be beneficial in many ways, it can also lead to some issues.

For example, while this reminder can motivate some people to use their limited time wisely, it can cause others to simply feel anxious instead. Similarly, while this reminder can help some people identify their goals in life, it can cause others to feel depressed instead, and to worry that everything they do will be ultimately meaningless.

As such, while ‘memento mori’ can be a useful principle to implement, it’s important to keep its potential limitations in mind, and only use it in situations where it does more good than harm. In the next section, you will see some tips that can help you with this, by showing you how to implement the concept of memento mori in a way that is as beneficial as possible.

How to implement ‘memento mori’

“Do not act as if you were going to live ten thousand years. Death hangs over you. While you live, and while it is in your power, be good.”

— From “Meditations“(Book IV, Passage 17), by Marcus Aurelius

As we saw above, using ‘memento mori’ as a reminder can be beneficial in a variety of ways, which makes it a rather versatile tool.

The basic way to implement this principle is to use it as a reminder that guides your thinking. For example, if something small bothers you, and you know that it shouldn’t, you can tell yourself “memento mori—this is too minor and temporary to be worth worrying about”. Similarly, if you struggle to decide what you should spend your time doing, you can ask yourself “memento mori—what do I really want to spend my limited time on?”.

Below, you will see some additional tips and considerations, that will help you implement the principle of memento mori as effectively as possible.

Understand the difference between death reflection and death anxiety

There are two main ways in which people generally think about the fact that they will die:

- Death reflection. Death reflection involves a relatively positive reaction to the idea that you will eventually die, which revolves around using the thought of your eventual death as motivation to examine your life and contemplate your goals. Individuals generally react in this manner when they use their ‘cold’, rational cognitive system to process the idea of death.

- Death anxiety. Death anxiety involves a relatively negative reaction to the idea that you will eventually die. Individuals generally react in this manner when they use their ‘hot’, emotional cognitive system to process the idea of death.

When using ‘memento mori’ as a reminder, your goal should be to promote death reflection and avoid death anxiety. To do this, you should try to consider the idea of death using your rational cognitive system as much as possible, by thinking through this concept in a rational and analytical manner.

For example, you can try to view your eventual death as a concrete reality rather than as a vague notion, and ask yourself specific questions about its implications, such as “what do I want my legacy to be after I die?”.

Furthermore, you can use various debiasing techniques, to help yourself achieve this. For example, you can use self-distancing techniques, such as using second-person language instead of first-person language when asking yourself questions about your goals. This could, for instance, involve asking yourself “how does this affect your goals?” instead of “how does this affect my goals?”).

Note: death reflection and death anxiety are distinct from simple death awareness (also known as mortality salience), since they’re not just about being aware that you will eventually die, but also about reflecting on this concept and having it actively affect your thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Memento mori and mortality cues

Mortality cues are things that trigger awareness of death in some way. Mortality cues can be anything, including a painting of the grim reaper or a video of an event where someone was in danger of dying.

The term ‘memento mori’ is, in itself, a type of mortality cue, and you can use other types of mortality cues to remind yourself of it. For example, some people choose to remind themself of ‘memento mori’ by wearing a related piece of jewelry, such as a memento mori necklace or ring. Others choose to carry some other token, such as a memento mori coin. Some people even go a step further, and get a memento mori tattoo, which serves as a permanent reminder of this concept for them.

Caveat about using memento mori

While ‘memento mori’ can be a useful principle, not everyone feels comfortable with it. As such, if you feel that reminding yourself of ‘memento mori’ causes you more harm than it does you good, even after you’ve done everything you can to implement it properly, then you should avoid using it as a reminder.

Alternatively, if you feel that this is an issue, you can also consider using a milder form of ‘memento mori’. For example, instead of reminding yourself that death is inevitable, you can frame it in a different way, such as “I only have a limited amount of time to do things each day”.

More information about memento mori

Quotes about ‘memento mori’

This section contains some of the notable things that people have said about the concept of ‘memento mori’ throughout history, starting with its use by ancient philosophers and followed by its use in more modern times. Note that in some of these quotes, the term ‘memento mori’ is mentioned explicitly, while in others only the underlying idea behind it is discussed.

“Don’t let yourself forget how many doctors have died, after furrowing their brows over how many deathbeds. How many astrologers, after pompous forecasts about others’ ends. How many philosophers, after endless disquisitions on death and immortality. How many warriors, after inflicting thousands of casualties themselves. How many tyrants, after abusing the power of life and death atrociously, as if they were themselves immortal. How many whole cities have met their end: Helike, Pompeii, Herculaneum, and countless others.

And all the ones you know yourself, one after another. One who laid out another for burial, and was buried himself, and then the man who buried him—all in the same short space of time.

In short, know this: Human lives are brief and trivial.”

— From “Meditations“ (Book IV, Passage 48), by Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, circa 170 CE.

“Hippocrates cured many illnesses—and then fell ill and died. The Chaldaeans predicted the deaths of many others; in due course their own hour arrived. Alexander, Pompey, Caesar—who utterly destroyed so many cities, cut down so many thousand foot and horse in battle—they too departed this life. Heraclitus often told us the world would end in fire. But it was moisture that carried him off; he died smeared with cowshit. Democritus was killed by ordinary vermin, Socrates by the human kind.

And?

You boarded, you set sail, you’ve made the passage. Time to disembark. If it’s for another life, well, there’s nowhere without gods on that side either. If to nothingness, then you no longer have to put up with pain and pleasure, or go on dancing attendance on this battered crate, your body—so much inferior to that which serves it.

One is mind and spirit, the other earth and garbage.”

— From “Meditations” (Book III, Passage 3), by Marcus Aurelius

“A trite but effective tactic against the fear of death: think of the list of people who had to be pried away from life. What did they gain by dying old? In the end, they all sleep six feet under—Caedicianus, Fabius, Julian, Lepidus, and all the rest. They buried their contemporaries, and were buried in turn.”

— From “Meditations” (Book IV, Passage 50), by Marcus Aurelius

“We plan distant voyages and long-postponed home-comings after roaming over foreign shores, we plan for military service and the slow rewards of hard campaigns, we canvass for governorships and the promotions of one office after another—and all the while death stands at our side; but since we never think of it except as it affects our neighbour, instances of mortality press upon us day by day, to remain in our minds only as long as they stir our wonder.

Yet what is more foolish than to wonder that something which may happen every day has happened on any one day? There is indeed a limit fixed for us, just where the remorseless law of Fate has fixed it; but none of us knows how near he is to this limit.”

— From “Letters from a Stoic” (letter number 101, “On the Futility of Planning Ahead”), by Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger, circa 65 CE.

“…let us so order our minds as if we had come to the very end. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life’s account every day. The greatest flaw in life is that it is always imperfect, and that a certain part of it is postponed. One who daily puts the finishing touches to his life is never in want of time. And yet, from this want arise fear and a craving for the future which eats away the mind. There is nothing more wretched than worry over the outcome of future events; as to the amount or the nature of that which remains, our troubled minds are set aflutter with unaccountable fear.”

— From “Letters from a Stoic” (letter number 101, “On the Futility of Planning Ahead”), by Seneca

“Do you likewise remind yourself that you love what is mortal; that you love what is not your own. It is allowed you for the present, not irrevocably, nor forever; but as a fig, or a bunch of grapes, in the appointed season. If you long for these in winter you are foolish. So, if you long for your son, or your friend, when you cannot have him, remember that you are wishing for figs in winter. For as winter is to a fig, so is every accident in the universe to those things with which it interferes. In the next place, whatever objects give you pleasure, call before yourself the opposite images. What harm is there, while you kiss your child, in saying softly, ‘To-morrow you may die’; and so to your friend, ‘To-morrow either you or I may go away, and we may see each other no more.’

‘But these sayings are ominous.’

And so are some incantations; but, because they are useful, I do not mind it; only let them be useful.”

— From the “Discourses of Epictetus” (Book III, Chapter 24), based on informal lectures by the Stoic philosopher Epictetus that were collected by his student Arrian, published circa 108 CE.

One notable story which features the concept of ‘memento mori’ involves a slave standing behind a victorious general during a procession celebrating the general’s achievements:

“He is reminded that he is a man even when he is triumphing, in that most exalted chariot. For at his back he is given the warning: ‘Look behind you. Remember you are a man.’ [‘Respice post te, hominem te memento’] And so he rejoices all the more that he is in such a blaze of glory that a reminder of his mortality is necessary.”

— From “Apologeticus” (chapter 33) by Christian author Tertullian (circa 200 CE), as quoted in “The Roman Triumph“, by English scholar Mary Beard (2007).

Though the veracity of this tale has been questioned, for example by English scholar Mary Beard in her book “The Roman Triumph“, it remains a tale that is often used in modern times to illustrate how the concept of memento mori can be used.

When it comes to the English language, the first use of ‘memento mori’ in print is attributed, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, to Shakespeare, who wrote the following:

“Bardolph: Why, Sir John, my face does you no harm.

Falstaff: No, I’ll be sworn; I make as good use of it as many a man doth of a Death’s-head or a memento mori…”

— From the play “Henry IV, Part 1” (Act III, Scene 3) by William Shakespeare (published circa 1597)

Since then, this concept was also mentioned in other literature. For example:

“Memento mori, remember death! This is a great saying. If we only bore in mind that we should inevitably die and that very soon, our life would be entirely different. If a man knows that he will die inside of thirty minutes, he will not do anything trifling or foolish in these last thirty minutes, surely not anything evil. But is the half century or so that separates you from death essentially different from a half hour?”

— From “The Pathway of Life: Teaching Love and Wisdom”, by Russian author Leo Tolstoy (1919)

And:

“And I think that we all, except perhaps nurses and doctors who see it all the time, have a primitive instinct to withdraw from death, even if we manage to conceal our pulling away. There is always the memento mori, the realization that death is contagious; it is contracted the moment we are conceived.”

— From “A Circle of Quiet” (Book 1 of “The Crosswicks Journals“), by American author Madeleine L’Engle (1972)

In addition, this concept has also appeared in other types of media. For example:

“Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Because almost everything — all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure — these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

— By American designer, inventor, and entrepreneur Steve Jobs, in a Stanford University commencement address (2005)

Note: ‘memento mori’ is sometimes assigned slightly different translations, which all share the same general meaning. This includes, for example, “remember that you will die”, “remember that you must die”, “remember that you have to die”, and “remember death”.

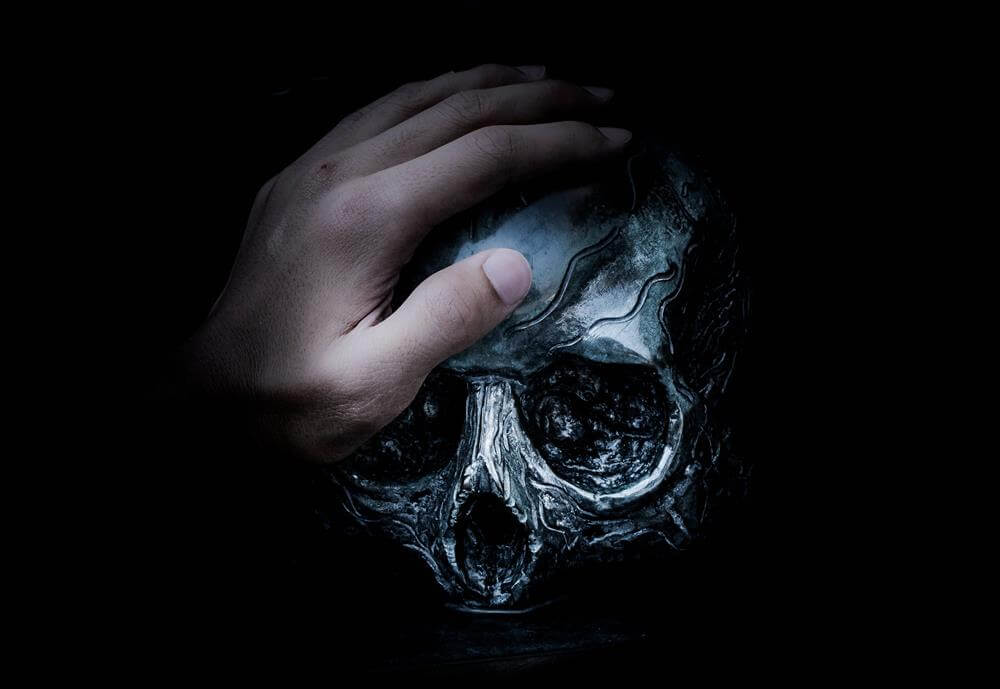

Symbols of memento mori in art

Throughout history, various symbols have been associated with the concept of memento mori, particularly when it comes to art. The symbol that is most strongly associated with memento mori is the human skull, but other symbols are also commonly associated with this concept, including hourglasses, clocks, candles, and flowers, which are all meant to remind people of the finiteness of their life.

In addition, there are also specific genres of art that are associated with the concept of memento mori.

One notable genre is the Danse Macabre, which focuses on the universality and inevitability of death. In this genre, a grim reaper is often featured as a personification of death, and is depicted accompanying a large group of people, from all hosts of life, to their death. This was intended to serve as a memento mori which reminds people that no matter their station in life, death will eventually come for them.

Another notable genre of art associated with memento mori is the Vantias, which focuses on still-life works, containing various symbolic objects that are meant to remind the viewer of their mortality, and emphasize the worthlessness of worldly pleasures. Such works of art often contain traditional memento mori symbols, such as the skull, together with symbols that are intended to represent worldly possessions, such as musical instruments. The name of this genre comes from the following biblical quote:

“Vanity of vanities, said Ecclesiastes: vanity of vanities, and all is vanity.” [vanitas vanitatum dixit Ecclesiastes vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas]

— Ecclesiastes 1:40 (in the Vulgate Latin translation)

Finally, some Latin phrases are also associated with the underlying concept behind ‘memento mori’. For example, the following phrases were sometimes inscribed on clocks, in order to serve as a reminder of the brevity of life:

- “vulnerant omnes, ultima necat”, which means “all [hours] wound, the last one kills”.

- “ultima forsan”, which means “perhaps the last [hour]”.

- “tempus fugit”, which means “time flies”.

Note: in some cases, the term ‘memento mori’ is used to refer directly to an object or painting which serves as a reminder of this concept.

Memento mori in religion

Memento mori and related concepts have appeared in various religions, throughout history.

For example, Buddhism has the concept of Maranasati, which involves being mindfully aware and reflective of death.

Judaism also mentions this concept, as can be seen in the following quote:

“For that which happens to the sons of men happens to animals. Even one thing happens to them. As the one dies, so the other dies. Yes, they have all one breath; and man has no advantage over the animals: for all is vanity.”

— Ecclesiastes, Chapter 3, Verse 19

Similarly, Christianity also discusses this concept:

“By the sweat of your brow will you have food to eat until you return to the ground from which you were made. For you were made from dust, and to dust you will return.”

— Genesis 3:19

Note, however, that different religions sometimes discuss this concept in different ways, and there can even be variability in terms of how this concept is used within the same religion.

For example, while this concept can be used to encourage people to consider their own morality in order to encourage them to make the most of life, it can also be used to encourage people to behave in a morally proper manner, as is evident in the following quote, that is discussed in Christianity:

“In all thy works remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin.” [in omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua et in aeternum non peccabis].

— Ecclesiasticus 7:40 (in the Vulgate Latin translation)

Related concepts

Memento vivere

Memento vivere is a Latin phrase that means “remember to live”. This phrase is frequently mentioned as a supposed contrast to ‘memento mori’, since it revolves around remembering to live your life, rather than remembering your inevitable death. However, both phrases generally lead to the same underlying conclusion, from a practical perspective, which is that you should remember to make the most of life and live it to the fullest.

‘Memento vivere’ is a more modern and less common saying than ‘memento mori’, and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, it first appeared in print in English in the following poem:

When life was young, in pensive guise

I made it a fantastic glory,

To pause and sentimentalize

O’er every sad “Memento Mori.”

Dear fourscore friend! In their dull place

How gladlier now I turn to thee,

With all thy cheery wit and grace,

Though bright “Memento Vivere.”

— From “A Day at Tivoli’”by John Kenyon (1849)

Note: ‘memento vivere’ is sometimes translated in other, similar ways, such as “remember living” or “think of living”.

Carpe diem

Carpe diem is a Latin phrase that means “seize the day”. It encourages people to focus on the present, appreciate the value of every moment in life, and avoid postponing things unnecessarily, because every life eventually comes to an end.

Memento mori is often associated with the concept of carpe diem, since both sayings encourage people to contemplate the inevitability of their death, and use that as motivation to make the most of life. In this regard, it can be useful to also implement the principle of ‘carpe diem’ together with ‘memento mori’, and some people might feel more comfortable focusing on the concept of ‘carpe diem’, since it’s formulated in a more positive manner, that’s less focused on death.

Tempus fugit

Tempus fugit is a Latin phrase that means “time flies”. It’s meant to remind you that your time is limited and continuously passing, both in general and when it comes to specific things such as pursuing your goals or being with the people you care about.

Similarly to ‘carpe diem’, the concept of ‘tempus fugit’ is also associated with the concept of ‘memento mori’, since both concepts are often used to encourage people to remember that the time that they have is limited.

Summary and conclusions

- Memento mori is a Latin phrase that means “remember that you will die”. It is meant to remind you of your own mortality, and of the brevity and fragility of human life.

- Using ‘memento mori’ as a reminder can be beneficial in a number of ways, such as by helping you figure out which goals you want to pursue, by prompting you to take action in a timely manner, and by helping you put your problems in perspective.

- For example, if something small bothers you, and you know that it shouldn’t, you can tell yourself “memento mori—this is too minor and temporary to be worth worrying about”. Similarly, if you struggle to decide what you should spend your time doing, you can ask yourself “memento mori—what do I really want to spend my limited time on?”.

- Some people might not feel comfortable with using memento mori as a reminder, for example because it causes them to feel anxious; in such cases, you can either avoid using this concept entirely, or you can use a milder formulation of it, such as “I only have a limited amount of time to do things each day”.

- Another thing you can do to make the most of the principle of ‘memento mori’, is to consider it in a rational, non-emotional manner, which you can accomplish by using various debiasing techniques, such as asking yourself questions about ‘memento mori’ in the second or third person (e.g. “memento mori—how do you feel about this issue?”).