Reflective practice involves actively analyzing your experiences and actions to help yourself improve at the things you do.

For example, an athlete can engage in reflective practice by thinking about mistakes that they made during a training session, and figuring out ways to avoid making those mistakes in the future.

Reflective practice can be beneficial in various situations, so it’s worthwhile to understand this concept. As such, in the following article you will learn more about reflective practice, and see how you can engage in it yourself, as well as what you can do to encourage others to engage in it.

Examples of reflective practice

An example of reflective practice is an athlete who, after every practice, thinks about what they did well, what they did badly, why they did things the way they did, and what they can do in the future to improve their performance.

In addition, examples of reflective practice appear in a variety of other domains. For instance:

- A student can engage in reflective practice by thinking about how they studied for a recent test and how they ended up performing, in order to figure out how they can study more effectively next time.

- A medical professional can engage in reflective practice by thinking about a recent procedure that they performed, in order to identify mistakes that they’ve made and figure out how to avoid making those mistakes in the future.

- A human-resources representative can engage in reflective practice by thinking about recent interviews that they conducted with potential new hires, in order to determine whether all the steps in the interview are necessary, and whether any other steps are needed.

The benefits of reflective practice

There are many potential benefits to reflective practice. These include, most notably, the following:

- Acquisition of new knowledge.

- Refinement of existing knowledge, for example by correcting current misconceptions.

- An improved understanding of the connections between theory and practice.

- An improved understanding of the rationale behind your actions, in terms of factors such as why you do the things that you do, and why you do things a certain way.

- Improvement of your goals and of the rules that you use for decision-making (this is also associated with the concept of double-loop learning).

- A better understanding of yourself, in terms of factors such as your strengths and weaknesses.

- Development of your metacognitive abilities, for example when it comes to your ability to analyze your thoughts more effectively.

- Increased feelings of autonomy, competence, and control.

- Increased motivation to act.

- Improved performance, for example due to learning how to take action in a more effective way, or due to having more motivation to take action.

These benefits can apply not only to the specific domain in which you engage in reflective practice, but also to other domains. For example, if a musician engages in reflective practice with regard to how they play their instrument, they might improve their understanding of their preferences as a learner, which could help them when it comes to their academic studies.

Finally, note that in some cases, reflective practice is viewed as not only beneficial, but outright crucial to people’s goals. As one scholar notes:

“It is not sufficient simply to have an experience in order to learn. Without reflecting upon this experience it may quickly be forgotten or its learning potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated. And it is generalisations which enable new situations to be tackled effectively.

Similarly, if it is intended that behaviour should be changed by learning, it is not sufficient simply to learn new concepts and develop new generalisations. This learning must be tested out in new situations. The learner must make the link between theory and action by planning for that action, carrying it out, and then reflecting upon it, relating what happens back to the theory.”

— From “Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods” by Graham Gibbs (1988)

Overall, there are many potential benefits to reflective practice, including a better understanding of the rationale behind your actions, increased feelings of control, and improved performance, and these benefits can extend to additional domains beyond the one in which you engaged in reflective practice.

How to engage in reflective practice

Broadly, reflective practice involves thinking about how you do things, and trying to understand why you do what you do, and what you can do better. As such, there are many ways you can engage in it, and different approaches to reflective practice will work better for different people under different circumstances.

One notable way to engage in reflective practice is to ask guiding questions. For example, when it comes to reflective practice in the context of a recent event, you can ask yourself the following:

- How did I feel while the event was happening?

- What were my goals?

- What were the main things that I did?

- What went well?

- What went badly?

- What should I do the same way next time?

- What should I do differently next time?

Similarly, you can engage in reflective practice through reflective writing, which can also take various forms, such as answering guiding questions, creating a detailed narrative of a recent event, or sketching a diagram to analyze your thoughts. This can be beneficial when it comes to improving your ability to reflect, and it also has the added benefit of giving you the option to review your original reflections, especially if you collect your writings in a consistent location, such as a reflection journal.

When deciding how to engage in reflective practice, it’s crucial to find the specific approaches that work best for you in your particular situation. This means, for example, that if you try to engage in reflective writing but consistently find that thinking aloud works better for you, then it’s perfectly acceptable to do that instead. Similarly, while peer feedback can facilitate reflection in some cases, it can also hinder it in others, so you should use it only if you find that it helps you.

Finally, keep in mind that it’s generally more difficult and time-consuming in the short-term to engage in reflective practice than to act without reflection, especially when it comes to reflecting as events are unfolding, and this can make people prone to avoiding reflection. Furthermore, the difficulties of reflective practice sometimes make it impractical, meaning that people must avoid it in certain situations. However, in cases where it’s possible to engage in reflection in a reasonable manner, doing so often ends up being beneficial in the long-term, both when it comes to performance, as well as when it comes to related benefits, such as personal growth.

Overall, you can engage in reflective practice in various ways, such as by asking yourself guiding questions about your actions, or by writing about your experiences. Different approaches to reflective practice will work better for different people under different circumstances, so you should try various approaches until you find the ones that work best for you.

The reflective cycle

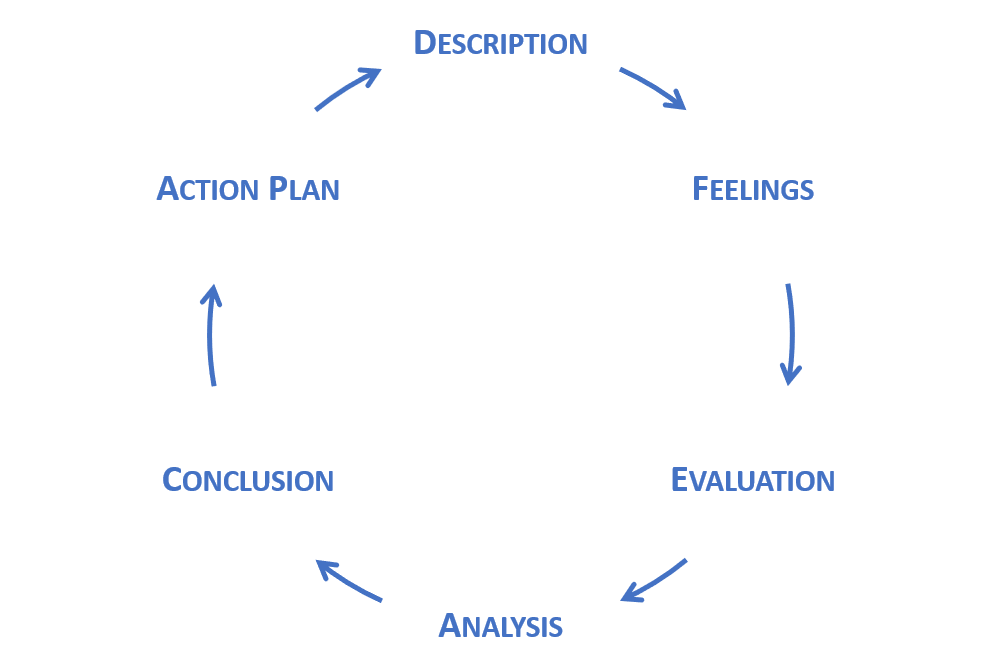

Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a process for guiding reflective practice. It involves the following steps, in order:

- Description. Describe what happened, without judgment or analysis. For example, you can ask yourself where you were, who else was present, and what happened.

- Feelings. Describe how you felt, what you were thinking, and how you feel now, again without judgment or analysis.

- Evaluation. Evaluate everything that happened, for example, by asking yourself what went well and what went badly.

- Analysis. Analyze the situation, to try and make sense of everything that happened. For example, you can ask yourself why the things that went well went well, why the things that went badly went badly, and why you acted the way that you did.

- Conclusion. Draw conclusions based on the information that you generated so far. Start with general conclusions, and then move on to specific ones that pertain to your particular situation. For example, you can start by forming general conclusions about how people act in certain situations, and then move on to form more specific conclusions about what that means for the type of situation that you’re in.

- Action plan. Figure out what you are going to do differently next time, based on everything that you’ve learned. For example, if you realize that things went badly because you’ve made a certain mistake as a result of carelessness, figure out how you’re going to act in the future to avoid making that mistake again.

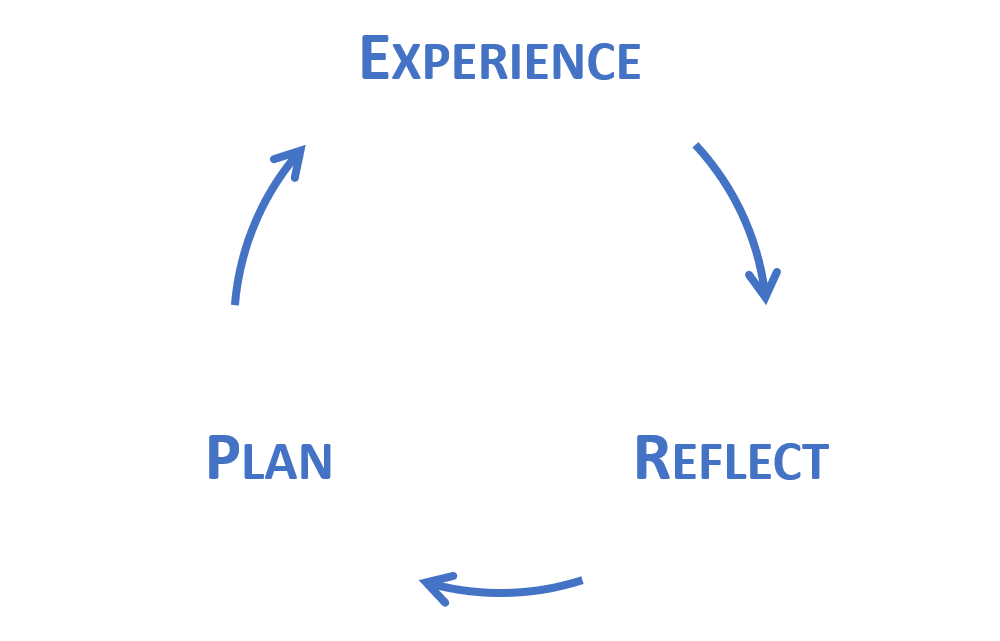

Note: in addition to Gibbs’ reflective cycle, there are other models that can be used to guide reflective practice, such as Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. These models generally revolve around the concept of experiential learning, which is learning that is based on experience (i.e., “learning by doing”).

Types of reflection

A distinction can be drawn between three types of reflection, based on your temporal relation to the event that you’re reflecting about. Based on this distinction, there are three main types of reflection:

- Anticipatory reflection. Anticipatory reflection is reflection that’s performed before an event occurs. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what might happen, what challenges you’re likely to face, how should you respond, and what you can do to prepare.

- Reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action is reflection that’s performed while an event is occurring. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what’s currently happening, whether things are going as expected, how you’re feeling, and whether there’s anything you should be doing differently.

- Reflection-on-action. Reflection-on-action is reflection that’s performed after an event has occurred. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what happened, what went well, and what you should have done differently.

These types of reflection are similar conceptually, though there are some minor differences between them. For example, when it comes to anticipatory reflection, you must rely on predictions of future experiences, rather than on those actual experiences or your recollections of them, though you can use your past experiences to inform those predictions. Similarly, when it comes to reflection-in-action, you might need to engage in reflection faster and while under heavier pressure, if you want to be able to use the reflect to inform your actions as the event in question unfolds.

Levels of reflection

You can engage in reflection in different ways and to different degrees. For example, when it comes to reflection, there’s a difference between simply asking yourself “did I do well?” and asking yourself “how well did I do, why did I do what I did, and what can I do better?”.

These different forms of reflection can be viewed as distinct from one another, and as different levels of reflection within a single hierarchy or continuum. A common example of how reflection might be categorized based on this is by differentiating between superficial reflection and deep reflection, where deep reflection involves reflection that is more in-depth in various ways.

From a practical perspective, what matters most is understanding that in different situations you might benefit from different levels of reflection. For example, in some cases, it might be preferable to engage in superficial reflection, and simply identify the fact that you’ve made a mistake, while in other cases, it might be preferable to engage in deep reflection, by figuring out why you’ve made a mistake and what you can do to avoid making it again.

Note: other terms are sometimes used to differentiate between superficial and deep reflection, such as shallow reflection or surface reflection (in place of superficial reflection), and thorough reflection (in place of deep reflection).

Using self-distancing to help reflection

In some cases, it can be beneficial to use self-distancing to aid the reflection process. This can help you get better insights into your actions, by reducing issues such as the egocentric bias, which can hinder reflection. To use self-distancing in this manner, you can do things such as the following:

- Ask yourself what advice would you give someone else if they were in the same situation as you.

- Avoid first-person language when considering your performance (e.g., instead of asking “what could I have done differently?”, ask “what could you have done differently?”).

- When considering events you were in, try to visualize them not only from your own perspective, but also from the perspective of other people involved, or from a general external perspective.

Reflective practice as a shared activity

It’s possible to engage in reflective practice as part of a shared activity. This type of reflection can take various forms, such as discussing your experiences with a group of other people, or having someone with expertise ask you guiding questions in order to help you reflect.

Shared reflective practice has both potential advantages and disadvantages. For example, shared reflection as part of a group might help people identify more issues with their actions than they would be able to identify by themself, as a result of being exposed to more perspectives. At the same time, however, this approach might also make the reflection process much more stressful for people who are shy.

Accordingly, it’s important to consider the potential advantages and disadvantages of the various approaches to reflective practice, when deciding whether to use shared practice in your particular circumstances, and if so then in what wait.

Note: a phenomenon that’s related to shared reflective practice is the protégé effect, which is a psychological phenomenon where teaching, pretending to teach, or preparing to teach information to others helps a person learn that information. Specifically, the protégé effect means that helping others engage in reflective practice can improve your own ability to do so, and can also help you when it comes to learning other things.

How to encourage reflective practice in others

To encourage others to engage in reflective practice, you can start by doing the following:

- Explain what reflective practice is.

- Explain why reflective practice is beneficial.

- Explain how to engage in reflective practice.

This can be guided by the material provided in the earlier sections of this article, on how to engage in reflective practice yourself.

Once you’ve done this, you can create an environment that is conducive to reflective practice, and help people engage in it, while keeping in mind that different people will benefit from different approaches to reflection. For example, some people might benefit from having someone go with them through each stage of the reflection cycle, while others will benefit more from simply being shown how reflection works and then being left to do reflect on their own.

Alternatively, you can also take a more externally driven approach to reflective practice, by guiding people through reflective practice, without fully explaining the concept to them.

Finally, note that you should generally avoid forcing the reflection process, or forcing people to “confess” what they’ve done wrong, since this can lead to ineffective reflection, as well as to various other issues. For example, when people know that they will be graded based on their responses during the reflection process, they might answer in a dishonest and strategic manner, by giving responses that they think the person evaluating them wants them to give. Similarly, this kind of forced reflection can also lead to issues such as increased stress, as well as increased hostility toward the reflection process and the people who guide it.

Accordingly, in cases where it’s possible and beneficial, you should allow people to make their reflections private. In addition, you should also avoid sticking to a strict reflection template in cases where doing so is counterproductive, and instead allow people to engage in reflection in the way that works best for them.

Related concepts

Two concepts that are often discussed in relation to reflective practice are reflexivity and critical reflection:

- Reflexivity describes people’s ability and tendency to display general self-awareness, and to consider themselves in relation to their environment.

- Critical reflection describes an extensive and in-depth type of reflection, which involves being aware of how your assumptions affect you, as well as examining your actions and responsibilities from moral, ethical, and social perspectives.

In addition, another closely related concept is reflective learning, which involves actively monitoring your knowledge, abilities, and performance during the learning process, and assessing them in order to find ways to improve.

The terms reflective practice and reflective learning refer to similar concepts, and because their definitions vary and even overlap in certain sources, they are sometimes used interchangeably.

Nevertheless, one notable way to differentiate between them is to say that people engage in reflective learning with regard to events where learning is the main goal, and in reflective practice with regard to events where learning is not the main goal. For example, a nursing student might engage in reflective learning when learning how to perform a certain procedure, whereas an experienced nurse might engage in reflective practice while performing the same procedure as part of their everyday routine.

Alternatively, it’s possible to view reflective learning as a notable type of reflective practice, which revolves around improving one’s learning in particular.

Overall, there is no clear distinction between reflective practice and reflective learning, and these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. However, potential distinctions between these terms are generally not important from a practical perspective, since they are unlikely to influence how the underlying concepts are implemented in practice.

Summary and conclusions

- Reflective practice involves actively analyzing your experiences and actions to help yourself improve at the things you do.

- A notable process that you can use to engage in reflective practice is Gibbs’ reflective cycle, where you (1) describe what happened, (2) consider what you were feeling and thinking during your experience, (3) evaluate what was good or bad about it, (4) analyze what else you can make of the situation, (5) draw both general and specific conclusions, and (6) create an action plan for the future.

- There are many potential benefits to reflective practice, including a better understanding of your actions, increased feelings of control, and improved performance.

- You can reflect in different ways in different circumstances, for example by going through deep reflection after events have concluded in some cases, and quickly reflecting while events are still unfolding in others.

- You can encourage others to engage in reflective practice by explaining how to do it and asking them guiding questions.